Over the course of a long gig-going life, there will inevitably be regrets about opportunities missed. Festivals in particular offer so many choices that there is bound to be the odd misstep. From the perspective of what happened in the following few months, I look back with a rueful shake of the head on being sat in a tent with a fellow fanzine writing friend at Reading Festival in August 1991 and agreeing that there was no point going to see Nirvana who were just a boring rock band. Ultimately, though, I have seen many high-quality bands of that ilk so from a musical point of view, I curse myself much more for not taking the chance to see Mulatu Astatke at Bowlie 2 in the winter of 2010. A chalet mate was about to cook dinner and my stomach took precedence over my ears. Had I realised at the time that Astatke had composed some of the amazing music that had caught my attention in Jim Jarmusch’s film, ‘Broken Flowers’, however delicious the food was I would have made a different decision.

Over the course of a long gig-going life, there will inevitably be regrets about opportunities missed. Festivals in particular offer so many choices that there is bound to be the odd misstep. From the perspective of what happened in the following few months, I look back with a rueful shake of the head on being sat in a tent with a fellow fanzine writing friend at Reading Festival in August 1991 and agreeing that there was no point going to see Nirvana who were just a boring rock band. Ultimately, though, I have seen many high-quality bands of that ilk so from a musical point of view, I curse myself much more for not taking the chance to see Mulatu Astatke at Bowlie 2 in the winter of 2010. A chalet mate was about to cook dinner and my stomach took precedence over my ears. Had I realised at the time that Astatke had composed some of the amazing music that had caught my attention in Jim Jarmusch’s film, ‘Broken Flowers’, however delicious the food was I would have made a different decision.

Subsequently, I have learnt much more about Astatke and his role as the father of Ethio-jazz, a journey that began after he was sent to Wrexham to study Aeronautical Engineering in the late 1950s. However, his farsighted headmaster recognised his talent on the trumpet and recommended that he devote his talents to music. Moving to London, he studied piano, clarinet and harmony, graduating with a degree from Trinity College of Music. After immersing himself in the jazz scene and playing at Ronnie Scott’s, he moved to America and became the first African student to enrol at the jazz-leaning Berklee College of Music in Boston, studying vibraphone and percussion. Inspired by how Duke Ellington and Dizzie Gillespie created their own type of jazz, he moved back to Addis Abada at the end of the 1960s with the intention of creating his own musical fusion. It utilised the four pentatonic modes he had grown up with alongside the structures he had learnt in America. He brought in vibraphone, electric keyboards, effects pedals, congas and bongos to produce Latin rhythms while also using traditional Ethiopian instruments in new ways, including the krar (lyre), masenqo (one string fiddle) and washint (penny whistle). It is this combination of the familiar with unexpected elements that makes his music both so rich and instantly appealing.

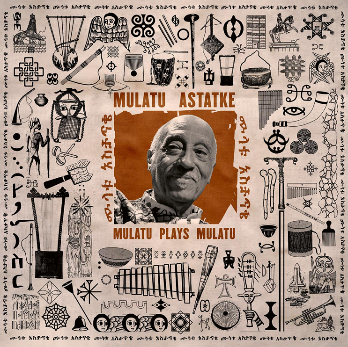

A lengthy career has been littered with notable events such as playing with Ellington in front of Haile Salassie, featuring heavily in the groundbreaking Ethiopiques series of albums and having his work sampled by the likes of Nas and Damian Marley, Kanye West and Madlib. ‘Mulatu Plays Mulatu’ is his first major studio album in ten years and is recorded between London and Addis Abada. It features his longstanding English band together with musicians from the Jazz Village club in Addis and sees him revisiting tracks from his career, giving them new arrangements, extended improvisations and heightened rhythmic complexity.

Over the course of eleven tracks, it weaves a relaxed magic. After emerging from an opening burst of dissonance, the first track, ‘Zelesenga Dewel’, gives a good indication of what is to follow. The snaking trumpet and sax lines that are the most immediately recognisable element of Astatke’s music lead. Vibraphone (invariably the most chilled sounding of instruments), piano, percussion and double bass give more of a big band feel than earlier Astatke work. The tune’s ten-minute duration is the longest on the record but it is comfortable throughout in allowing itself time to develop a mood. ‘’Kulun’ is one of the shortest journeys at only three and a half minutes, its percussion prominent on what is a take on a wedding song in the uniquely Ethiopian anchi-hoye scale.

There are versions of three pieces that appeared on ‘Ethiopiques 4’, an issue devoted exclusively to Astatke and which serves as a wonderful introduction to his work: ‘Netsanet’ is extended to eight minutes and mesmerizingly matches horns with piano playing that ranges from calm to atonal and what may well be masenqo; running to a similar length, ‘Yekermo Sew’, was my induction into Astatke’s music and the heart still leaps on hearing its now familiar sax and trumpet lines; and the album closer ‘Yekatit’ has the funkiest and most buoyant groove.

There are a variety of moods on offer from the air of both mystery and drama that pervades ‘Azmari’ to ‘Chik Chikka’ with a title that gives an indication to this number’s percussive nature and which features some pleasing double bass action and builds some heart-racing momentum. Aptly, ‘The Way To Nice’ has a refreshing lightness to it. ‘Motherland Intro’ is a mournful 96 seconds of strings, vibes and piano before ‘Motherland’ foregrounds emotive trumpet over a cool tempo backing. In contrast, the self-titled ‘Mulatu’ develops a Latin groove, albeit far from frenetic.

Over the course of an hour, ‘Mulatu Plays Mulatu’ has much to offer. It is an album for sitting down and luxuriating in thoroughly. Beforehand, I wondered whether there was a need for new versions of tunes that I already loved but that is answered in the affirmative by a mature record that manages to embrace the ancient and modern, which is hypnotic in moods, relaxed yet emotive, a journey into his unique and influential world.

Mulatu Astatke: Mulatu Plays Mulatu – Out 26 September 2025 (Strut)