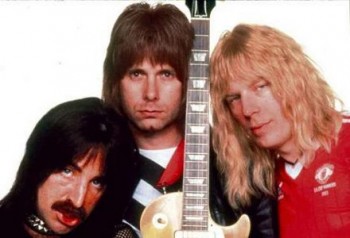

The year is 1984. Hack documentarian Marti DiBergi is interviewing world famous band Spinal Tap about their reaction to the succession of dreadful reviews written about their albums. He awkwardly states, ‘The review you had on Shark Sandwich was merely a two-word review… “shit sandwich,”’ to the bemusement and horror of the band. They exclaim, ‘That’s not real is it? You can’t print that!’

The year is 1984. Hack documentarian Marti DiBergi is interviewing world famous band Spinal Tap about their reaction to the succession of dreadful reviews written about their albums. He awkwardly states, ‘The review you had on Shark Sandwich was merely a two-word review… “shit sandwich,”’ to the bemusement and horror of the band. They exclaim, ‘That’s not real is it? You can’t print that!’

Of course, the scene is fictional. But the scenario is not so far from the truth. Following the release of movie This is Spinal Tap, a “rockumentary” satirising the music industry of the time, Musician Magazine* reviewer J.D. Considine gave short-lived super-group GTR’s eponymous debut album a similarly vicious two word review: ‘GTR – SHT.’ This negative piece of criticism was cruel but many found it humorous, becoming Considine’s most notable and notorious review. Although oddly in this case, the review helped sales of GTR’s album, for some musicians, a bad review can be a hurtful and damaging experience.

According to the law, a reviewer can say anything provided it is accurate, not malicious, based on provably true facts, and is clearly the writer’s opinion. As long as all these conditions are met, a reviewer can express their opinion freely and will be protected from a defamation lawsuit. However, the comments do not have to be fair, and so can be incredibly harmful to an artist’s reputation or career. This raises a serious ethical question for journalists who choose to review musical works – is it ever justified to express negative opinions if they threaten the career or wellbeing of an artist?

Journalist Gary Flockhart certainly believes so. The Edinburgh Evening News music writer hit headlines in November after being ‘banned’ from Noel Gallagher’s gig, in retaliation for an unfavourable review of his latest album, High Flying Birds. Flockhart wrote that the album was a ‘letdown’ that sounded ‘a lot like a collection of Oasis B-sides.’ He added, ‘any argument that Noel is Britain’s best song-writer died a long time ago.’ Gallagher’s PR team subsequently refused to supply him with any tickets to the gig, stating in an email that: ‘That piece you wrote about him last week didn’t exactly help your cause to be honest.’ In his own paper, Flockhart later ranted, ‘This is a man who has spent his entire career slagging off other artists – he obviously doesn’t like it when the shoe is on the other foot.’

Gallagher argued in his Huffington Post blog he had nothing to do with the situation: ‘There was also a story in one of the local newspapers that I’d had some hairdresser-turned-journalist banned from the gig… A ludicrous claim.’ Yet this is not the first time the Gallagher brothers have lashed out at critical journalists. In 2007 Liam mocked one reviewer for the Aberdeen Evening Express by sarcastically chatting with the audience, in response to criticism that he did not engage with the crowd at his concerts. Similarly, in 2009 Manchester Evening News columnist Angela Epstein complained about Oasis playing in her local park, prompting Noel to brand her a ‘ginger whinger’ and ‘joyless old husk.’

A month after the fiasco, Flockhart is surprisingly calm about the whole situation, believing it to reflect far worse on Gallagher than himself. He says: ‘If you’re earning thousands for an album like Noel Gallagher you would imagine that you’d build up a thick skin and you probably wouldn’t read as many reviews.’ Despite the controversy, it is evident Flockhart will continue to exercise his right to freedom of speech, explaining that in his opinion, negative reviews are just as important as positive ones: ‘It’s probably better to be talked about than not talked about… I don’t think it would be a good to give someone a good review based on their reputation if you personally didn’t like them. You’ve got to say what you feel.’

For some musicians however, Gallagher’s reaction is understandable. The critical mauling of their handiwork is a serious matter and can lead to feelings of low self-esteem, changes in direction or even a career crisis. A young band from Leeds, who wished to remain anonymous, spoke about their hurt caused by a bad review: ‘We just didn’t get it and felt dejected that we were trying to do something different…We did feel less confident about our style and tried to analyse how our differences could be a problem… it was a dark time.’

An artist who knows these trials and tribulations of media scrutiny only too well is Fyfe Dangerfield (pictured), soloist and frontman of indie-rock band the Guillemots, who spares a few minutes from his Crewe concert to speak about his experience.

An artist who knows these trials and tribulations of media scrutiny only too well is Fyfe Dangerfield (pictured), soloist and frontman of indie-rock band the Guillemots, who spares a few minutes from his Crewe concert to speak about his experience.

Dangerfield walks into the venue in a very bizarre ensemble of clothes. His frame is hidden by a hugely oversized Peruvian jumper, a baggy pair of McKenzie tracksuit bottoms, and dirty yellow pair of pumps. The look is completed with archaic, thick rimmed brown glasses and a full beard, much to the amusement of the management, who sniggers: ‘You can’t go on like that, mate.’

For the Guillemots frontman, public image is a growing concern, after a spate of reviews by journalists caused him to become uncomfortable with his own style. He says: ‘We used to dress up quite strangely for photo shoots and then we saw more and more reviews describing us as wacky and quirky and it really started getting to me… and then on for photo shoots we started dressing much more normally. It’s the same with music.’

This is not the only time the avant-garde band has struggled with criticism. Following a Mercury Music Prize nomination for Guillemots’ first album, Through the Window Pane, third record Walk the River received mixed reviews and even a backlash from the producer over its hour-long length. After a cutting review by BBC writer Tom Hocknell that stated the Guillemots’ ‘self-indulgence completely loses the listener,’ it is understandable that Dangerfield finds it damaging to read reviews at all. He says: ‘If I was asked for advice for people who were starting out, I’d say just don’t read reviews. What matters is that you’re doing this because you have a vision that no one else in the world has.’

But Dangerfield thinks that in reality, reviews have little effect on a band’s long term career: ‘If you look back through history a lot of bands that didn’t get great reviews are the ones that people are listening to now.’ And he has a point. In 2006 NME declared the Stone Roses self-titled debut album to be the best indie record of all time, despite initially slating it in 1989. On their website they apologised: ‘Now we don’t get it wrong at NME that often, but this was a clanger.’ Similarly, heavy metal pioneers Black Sabbath were panned by music critics, with one reviewer rubbishing them as ‘bubblegum Satanists’ and another claiming that album was ‘camp, like a horror movie.’ The album has since been ranked 130 in Rolling Stone’s ‘500 Greatest Albums of All Time.’

Fyfe truly believes that the best compositions are those which take time to grow on the listener. ‘You often find that records that get amazing reviews are sometimes the records that you listen to immediately and are incredible but they’ll wear off quickly. […] The great records [are] the ones that kind of creep up on you. You can’t get that from coming to it by a reviewer’s perspective.’ Dangerfield highlights an important point. Maybe in order for reviewers to act more fairly, they should follow suggestions by artists as to how much listening time an album is given.

After the interview, Fyfe retreats to the dressing room and emerges in a disappointingly normal outfit, of black skinny jeans and a horizontal black and white striped shirt for a promotional photo shoot. It appears that the condemnation of the critics is still distressing him, and is a stark reminder of just how affecting a review can be on a musical artist. This is not just unique to Dangerfield. Fellow midlands indie-rockers The Twang commented, ‘You just shouldn’t listen to what the media are saying, you should get on with your own thing. We’ve had bad album reviews and we know the reviewers who review them aren’t going to like our band. It’s a losing battle straight away.’ They clearly believe something needs to done about close minded reviewers, and they may be in luck.

Since 2009, the internet has been set ablaze by claims made by American reviewer Christopher R. Weingarten that the music journalism industry is dead. This is the result of the rise of online independent music blogs, which provide reviews at a greater breadth, depth and speed. Although many are amateur pages created purely for personal enjoyment, a number of blogs claim to offer an alternative to the mainstream music media, and provide a fairer platform for artists. Simon Poole is one such music blogger who believes that it is time for a more ethical approach to reviewing musicians.

Poole is the editor of online music blog Silent Radio, and makes it pretty clear in the page’s manifesto what he believes to be unethical about the music press. He writes: ‘We believe that the majority of the music press has become smug, superior, cynical, negative, bitchy… they treat music as a commercial product, when it should be treated with care and passion.’

Poole invites music loving members of the public to join his army of reviewers, in an attempt to create a fairer music platform. He asks to meet in a peculiar café in Manchester’s unconventional Northern Quarter, where he reveals the kind of writer he prefers to recruit. ‘I want people who have a passion for music, not people with a passion for slagging people off… Our policy is that if a review is bad, you have to say why.’ He adds, ‘Always leave any preconceptions at home… to try and listen with fresh ears. A lot of reviewers don’t because they enjoy looking for the bad things.’

However, Poole believes that musicians have an ethical responsibility as well as reviewers. Just as reviewers must write accurately and without malice, musicians must accept the journalist’s right to express their opinion freely, provided it is their honestly held belief. This is an issue he recently faced when a band reacted negatively to one of the website’s reviews. Poole recalls: ‘He asked me to remove the paragraph from the website, to which I said I’d be happy to do that, but then if any of our reviewers wrote a good review, that would also not be included on the website… If you want somebody to have an opinion, you can’t then say whether they can have a good one or a bad one… I think [Gary Flockhart] should be proud about being snubbed from the gig for saying what he believes.’ Poole clearly believes that although the press should give musicians a platform and not criticise for entertainment purposes, in return for publicity artists must accept negativity as well as praise.

It is obvious that although a poor review can damage an artist’s self confidence, reputation or even career. But before Poole retreats back to the blogging universe, he has a few rousing words of encouragement for such aspiring musicians: ‘If a bad review comes along, definitely don’t stop: keep on playing no matter what anyone says. People shouldn’t be picking up guitars or writing lyrics to get a good review. They should be picking up guitars because they love playing it. And they should carry on doing it no matter what.’

It seems that despite the damage it can cause, there is little opposition to journalists expressing negative opinions about musicians. Yet it is clear that more can be done to make reviewing a more ethical and fair experience. Perhaps, as Fyfe Dangerfield suggests, journalists should have to listen to an album for a certain time before they can judge it. By coming at an album from a ‘reviewer’s perspective,’ he argues that journalists will always be ‘looking for things to praise or fault,’ something that may be eradicated by listening with ‘fresh ears.’ Simon Poole calls for an end to reviews which are overly harsh without adequate reason. His belief is that if something is bad, you must explain why. Gary Flockhart, rather, believes the most important thing is to express yourself, no matter what.

Despite the debate, the future of such criticism is uncertain. Following Flockhart’s media storm, how many more journalists will risk such a showdown just to get their views heard? And how long before other reviewers follow Poole and Weingarten’s lead, departing the print world for blogging? As the demand for music publications continues to decline, and the surge in online critiques continues, perhaps this is a situation which will no longer need to be reviewed.

*article corrected/updated with information kindly supplied by J.D. Considine.

The GTR review you cite was written for Musician Magazine. It ran in a column called Rock Short Takes, the operative word being “short.” The idea was to make a telling point in as few words as possible; reviews in the section ran no more than 60 words. To complain that the reviews should have been longer and more detailed is to miss the point entirely.

As for Simon Poole’s call “for an end to reviews … which are overly harsh without adequate reason,” it’s worth noting that there were plenty of reviews enumerating the failings of GTR’s debut. Apart from length, the main difference between those and mine is that people still remember what I wrote.

I think this is a great article, and I totally agree with the conclusion.

As a musician, I know it can be hard to take criticism but it’s also a good way to face up to your weaknesses if you really genuinely want to improve. As a defence mechanism, it’s important to understand how diverse personal music tastes really are – as it’s sometimes just a matter of taste that leads to a bad review.

As a reviewer, I try to get across when something is good, well executed etc – especially when I DON’T like it, because the last thing I want to do is put people off following their own instincts. I have had a few emails from people who I have reviewed and they do often either ask for elaboration on the criticism, or simply accept it – in an interview, I mentioned the outro of a particular track and the guy held his hands up and agreed that they had got it wrong.

No record is perfect and often the musicians who made it will be the harshest critics in many respects – but it will undoubtedly be a very personal project. I try not to disrespect that – but sometimes, people do make some truly terrible music. If I am unfortunate enough to have that drop on to my desk, I can either lie – which does a disservice to anyone who might read my review – I can refuse to review it – which even as an amateur is unprofessional – or I can write a bad review. I don’t take pleasure from it, and I don’t do it lightly. Most importantly, I don’t do it if I don’t believe it.

As I said – good article 😀